Aikido Sensei

History of Aikido

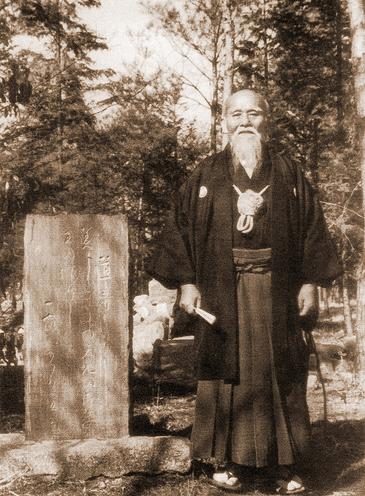

Aikido's founder, Morihei Ueshiba, was born in Japan on December 14, 1883. As a boy, he often saw local thugs beat up his father for political reasons. He set out to make himself strong so that he could take revenge. He devoted himself to hard physical conditioning and eventually to the practice of martial arts, receiving certificates of mastery in several styles of jujitsu, fencing, and spear fighting. In spite of his impressive physical and martial capabilities, however, he felt very dissatisfied. He began delving into religions in hopes of finding a deeper significance to life, all the while continuing to pursue his studies of budo, or the martial arts. By combining his martial training with his religious and political ideologies, he created the modern martial art of Aikido. Ueshiba decided on the name "Aikido" in 1942 (before that he called his martial art "aikibudo" and "aikinomichi").

On the technical side, Aikido is rooted in several styles of jujitsu (from which modern judo is also derived), in particular daitoryu-(aiki)jujitsu, as well as sword and spear fighting arts. Oversimplifying somewhat, we may say that Aikido takes the joint locks and throws from jujitsu and combines them with the body movements of sword and spear fighting. However, we must also realize that many Aikido techniques are the result of Master Ueshiba's own innovation.

On the religious side, Ueshiba was a devotee of one of Japan's so-called "new religions," Omotokyo. Omotokyo was (and is) part neo-shintoism, and part socio-political idealism. One goal of omotokyo has been the unification of all humanity in a single "heavenly kingdom on earth" where all religions would be united under the banner of omotokyo. It is impossible sufficiently to understand many of O Sensei's writings and sayings without keeping the influence of Omotokyo firmly in mind.

Despite what many people think or claim, there is no unified philosophy of Aikido. What there is, instead, is a disorganized and only partially coherent collection of religious, ethical, and metaphysical beliefs which are only more or less shared by Aikidoists, and which are either transmitted by word of mouth or found in scattered publications about Aikido.

Some examples: "Aikido is not a way to fight with or defeat enemies; it is a way to reconcile the world and make all human beings one family." "The essence of Aikido is the cultivation of ki [a vital force, internal power, mental/spiritual energy]." "The secret of Aikido is to become one with the universe." "Aikido is primarily a way to achieve physical and psychological self- mastery." "The body is the concrete unification of the physical and spiritual created by the universe." And so forth. At the core of almost all philosophical interpretations of Aikido, however, we may identify at least two fundamental threads: (1) A commitment to peaceful resolution of conflict whenever possible. (2) A commitment to self-improvement through Aikido training.

Aikido was first brought to the rest of the world in 1951 by Minoru Mochizuki with a visit to France where he introduced aikido techniques to judo students. He was followed by Tadashi Abe in 1952 who came as the official Aikikai Hombu representative, remaining in France for seven years. Kenji Tomiki toured with a delegation of various martial arts through fifteen continental states of the United States in 1953. Later in that year, Koichi Tohei was sent by Aikikai Hombu to Hawaii, for a full year, where he set up several dojo. This was followed up by several further visits and is considered the formal introduction of aikido to the United States. The United Kingdom followed in 1955; Italy in 1964; Germany and Australia in 1965. Designated "Official Delegate for Europe and Africa" by Morihei Ueshiba, Masamichi Noro arrived in France in September 1961.

Aikido makes use of body movement (tai sabaki) to blend with uke. For example, an "entering" (irimi) technique consists of movements inward towards uke, while a "turning" (tenkan) technique uses a pivoting motion. Additionally, an "inside" (uchi) technique takes place in front of uke, whereas an "outside" (soto?) technique takes place to his side; a "front" (omote?) technique is applied with motion to the front of uke, and a "rear" (ura) version is applied with motion towards the rear of uke, usually by incorporating a turning or pivoting motion. Finally, most techniques can be performed while in a seated posture (seiza). Techniques where both uke and nage are sitting are called suwari-waza, and techniques performed with uke standing and nage sitting are called hanmi handachi.

Thus, from fewer than twenty basic techniques, there are thousands of possible implementations. For instance, ikkyō can be applied to an opponent moving forward with a strike (perhaps with an ura type of movement to redirect the incoming force), or to an opponent who has already struck and is now moving back to reestablish distance (perhaps an omote-waza version). Specific aikido kata are typically referred to with the formula "attack-technique(-modifier)". For instance, katate-dori ikkyō refers to any ikkyō technique executed when uke is holding one wrist. This could be further specified as katate-dori ikkyō omote, referring to any forward-moving ikkyō technique from that grab.

Atemi are strikes (or feints) employed during an aikido technique. Some view atemi as attacks against "vital points" meant to cause damage in and of themselves. For instance, Gōzō Shioda described using atemi in a brawl to quickly down a gang's leader. Others consider atemi, especially to the face, to be methods of distraction meant to enable other techniques. A strike, whether or not it is blocked, can startle the target and break his or her concentration. The target may also become unbalanced in attempting to avoid the blow, for example by jerking the head back, which may allow for an easier throw. Many sayings about atemi are attributed to Morihei Ueshiba, who considered them an essential element of technique.

Philosophy

Ask a Chinese what is 'chi/qi' and you will get as many answers as you would asking an Aikidoka how to perform a kokyunage. A common answer is that chi refers to a particular mental and physical state that exhibits in a psychophysiological power associates with blood and breath. A chinese philosopher will talk about this microcosmical 'matter-energy' which is fundamental in forming and governing the universe. A traditional chinese physician, usually also a taoist by education, speaks about a microbiomaterial that circulates within the body, maintaining the living force that makes the body function. The chinese will probably accept any of these definitions in a 'matter-of-fact' manner and do not expect questions or disagreements concerning the meaning of chi. Of course this does not mean that they actually had a very accurate idea about the meaning of chi or that everybody knows exactly in what context one means when one talks about chi. In fact, the chinese probably means all of the above definitions, and more. This raises immediate problem for the western mind which makes clear distinctions between matter/mind, material/nonmaterial, physical/psychological/ physiological etc.. However one disagrees with the chinese blatant disregard for the cartesian dichotomy, this is in fact the way in which the chinese conceptualizes chi, or any other phenomena at all. Furthermore, they seems to be happy to trade off the analytical clarity for the imaginative richness.

When the chinese cosmic system which uses chi to explain the structure and function of virtually every phenomenon in the universe finally got transmitted to Japan in the seventh century, it had the shinto and tendai buddhist flavours added on. Unfortunately, or fortunately, the meaning of chi/ki did not get any clearer crossing the japanese sea. At any rate, from the oldest extant japanese work on traditional medicine, Ishopo by Tamba no Yasuyori, in the tenth century to modern works such as 'Qi: From the Analects to the New Science' by Maruyama Toshiaki, 'Qi: the Flowing body' by Harada Jiro one can see that both japanese and chinese traditional medicine share a basic conception of what it means to be fully human. Life is constituted by ki (in the sense of breath and energy), a force that manifests in respiration and that can be felt circulating within the body. Similarly, japanese drugs and concoctions are aimed specially at nourishing ki and enhancing its functioning.

Akido, a japanese martial art developed by master Mohirei Ueshiba earlier this century makes heavy use of the concept of ki. Aikido is one of the more spiritual martial arts and has been considered as 'moving zen'. The name Aikido means 'the way of harmony of ki'. Just exactly what is this ki that one supposes to harmonize with is a controversial topic among Aikidoka's. Some believes that the physical entity ki simply does not exist. Instead, the spirit, the intention, the bio-physico-psychological coordination through relaxation and awareness are concepts being used in the teaching. These Aikidoka's sometime tend to frown upon the philosophical/spiritual aspect of ki. Other Aikidoka's believe that ki does exist as a physical entity and can be transmitted through space. They, on the other hand, make use of concepts such as ki of the universe, extending ki etc.. By citing these two extremes, the author does not wish to imply that the 'truth' lies somewhere in between. But the fact of the matter is that there is a large portion of Aikidoka who are still, and no doubt will continue be, on their 'quest for ki'.

The task is not simple since many sensei's are reluctant to talk about ki. Those who do, do it in a very oriental way: full of metaphor, image and lack of clarity. The aim of this article is surveying the writting and teaching of Kaiso, his deshi's: Ueshiba, Tohei, Yamada, Shioda, Saito, Saotome, Nadeau, Dobson, Homa ... (listed in no particular order) to find out what they did mean when they mentioned the concept ki, or to find out whether one can come up with a definite answer at all. For the sake of simplicity, let's propose three simple definitions of ki:

Ki: the principle that governs the universe AND the individual, the cosmic truth.Ki: the action from a particular state of mind and body that can have physical/psychological/physiological effect.

This ki can be expressed, and hence, perceived through physical apprearance, behaviour, and body language.Ki: similar to (2). However this ki can be expressed and perceived by means including but not limited to those listed in (2).

One can see that from (1) to (3) the degree of abstract decreases while the physical component increases. The meaning of ki of course is not limited by the individual or combined definitions mentioned above.

Writings and Teachings of Saito, Yamada, Shioda, Homma, Nadeau and Dobson:

Among the available Aikido literatures from Kaiso's deshi's, "Traditional Aikido" by Morihiro Saito sensei stands out as a classic. Nevertheless, in this five-volume work, the concept of ki is discussed only briefly: "Ki: the vital force of the body. Through Aikido training, the ki of a person can be drawn in increasing amount from the universe. In practice, ki is directed before body movement takes place." A short description of a series of exercises for ki flowing can be found in his later work "Aikido, its heart and appearance" where one "causes partner's ki to flow out (fluid)" and "calling out your partner's ki and linking it to yours". Yoshimitsu Yamada sensei, a marvelous Aikido technician, in "The New Aikido Complete" is even less specific about ki. He refers to ki as "the power of the spirit of the mind that we all possess but which we use only on rare occasion." There is no noticable mention of ki in the work of Gozo Shioda sensei, the founder of Yoshinkan Aikido.

These sensei's are accomplished Aikidoka's in every sense of the word. Saito sensei's profound knowledge about Aikido techniques especially his contribution to the jo, bokken kata's is well respected in Aikido and aiki-jitsu circles. Shioda sensei's flawless and spontaneous techniques can only be compared with the equilibrium and tranquility reflected in chinese landscape paintings. It is hardly possible that these masters, who studied with the master of ki himself, are ignorant of the importance of ki. One can hypothesize that these sensei's feel that the teaching of ki, whatever their definitions are, has no place in a technical manual and is best left unspoken. Andvanced students should experience and define the essence of the art themselves with the guidance of the sensei. This style of teaching, known as shinin (imprinting of the heart), is not foreign to the oriental. The saying "A special transmission outside the Scriptures, no dependence upon words and letters" sums up the fundamental of Zen teaching. As Shioda sensei wrote "They (martial arts) must not become mere intellectual exercises, the fundamental budo 'conduct' must not be treated lightly, and the 'way of technique' must not be neglected as a form of spiritual and physical training", he wished to emphasize the idea that the essence of Aikido - ki - would express itself to those who practice and follow basic techniques diligently. This sentiment seems also to be shared by Doshu in his interview with Stan Prannin.

The sincere and direct approach in "Aikido for Life" has made Homma sensei's book an excellent introduction to what it takes and what it tastes like to be an Aikidoka. Aikido for Life is not a technical manual per se, albeit several techniques and exercises were included, but rather a reflection on the physical and mental training process of Aikido. Homma sensei's book reflects his honest feeling about the art and the way it should be practiced. He performed an irimi to many conceptions and misconceptions in Aikido. Homma sensei devoted the whole second chapter to the discussion of ki, which he believes does not exist. "The word ki is made of two letters, 'k' and 'i' nothing more. Of course you know how difficult it is to undestand something that can only be imagined. Some try to describe this thing that doesn't exist by letting their explanations drift into the realm of mystery. The mystery of ki has been deceiving many students"

To Homma sensei, ki has no color, shape nor weight and cannot be shown by ki believer simply due to the fact that ki as a physical entity does not exist. Homma sensei himself however, does not come up with the definition of ki himself as it seems not to be within the scope of his book. Instead, he urges one to dicsover ki "through daily practice inside and outside the dojo" but not "adopting another's definition blindly." Aikido according to Homma sensei is the "training of the mind" which expresses itself through breathing. When one's mind, body movement, and breathing is in harmony with the surroundings, one experiences the true meaning of Aiki. In this aspect, Homma sensei's concept of ki seems to be similar to definition (2) mentioned above. Homma sensei credits several technical accomplishments such as 'unbendable arm', 'unliftable body' to consistent practice and rejects the contribution of the "mysterious power" of ki. However, he also credits the benefits of several Aikido exercises, such as nikkyo and kotegeashi wrist warm up, and practices such as open hand, back rolles to shiatsu (acupressure). This seems somewhat contradictory. The concepts of keiraku (chinese: jingluo, english: meridian), rokuzo (liuzang, six yin organs), roppu (liufu, six yang organs) mentioned in Homma sensei's book are those discovered/invented by chinese traditional medicine. From this perspective, shiatsu inherited its entire theoretical foundation from acupuncture. The concepts of channels existing in human (and animal) body and their associated ying and yang organs (which do not necessarily have the equivalence in western medicine) are unique to chinese traditional medicine. Their sole purpose is to circulate chi within the body. The chi mentioned here is a physical entity as defined earlier according to chinese traditional medicine. One cannot use these concepts without accepting their raison d'e^tre. It seems that Homma sensei has denied the existence of the physical aspect of ki in one context only to use it in another.

Among O sensei's first american deshi is Robert Nadeau sensei who came to study with the master in his late seventies. Nadeau sensei, being profficient in several martial arts, has profound impact on his students not only thought his super physical techniques but also his dynamic approach by way of harmoninzing physical and mental concepts, action and comtemplation. Since there is no literature available by Nadeau sensei, his teaching will be extracted from the works of two of his decorated deshi's : Richard Strozzi Heckler and George Leonard.

In "The Ultimate Athelete", Leonard sensei describes a typical Energy-Body workshop pioneered by Nadeau sensei. The workshop begins with the assumption that "a field of energy exists in and around each human body". This energy is ki, "a single manifestation that includes emanations that can be measured by our present science, plus other esoteric or metaphorical amanations". One of the exercise in the workshop is "sensing the energy body" where partners stand with arms extending towards each other. When one 'feels' the energy from one's partner, one is asked to move apart to find out how far away one can still sense the energy connection. It is also obvious from other exercises that Nadeau sensei's idea of ki includes definitions (2) and (3).

"The Anatomy of Changes" by Heckler sensei portrays his effort to utilize Aikido principles in psychotherapy. The book describes the hara as "a point two inches below the navel, as the center of gravity and the place where ki (or life energy) originates". One can "feel or imagine a warmth in this area" to center oneself. To "ground" oneself (feel the connection between the body and the ground), one extends ki by feeling or imagining one's energy as "a strong flowing current that moves from your belly through your pelvis and legs, deep into the earth". Similarly, "unbendable arm" is done by feeling or imagining that "a current of powerful energy flowing through and out of this arm for a distance of a thousand miles. Your arm is like a conduit for a limitless and far-reaching energy that effortlessly flows through it. When you start to feel tingling, vibrating, or streaming sensations in your body and arms, continue to relax, and allows these sensations to join the current that is flowing through your arm". Again, this way of conceptualizing ki has more overlap with definition (3) than (2).

Terry Dobson sensei received the mission from O sensei to spread the spirit of Aikido to his people when he was one of Kaiso's last uchi deshi's. His life was the proof for the fulfillment of that promise as he refers to himself as a "ki mechanic". His only written work left is "Aikido in Everyday Life" though he has "imprinted the hearts" of many by his teaching. In "Aikido in Everyday Life" Dobson sensei refers to the one point "where one should be living ... it is the 'organ' which can sense attack faster than the intellect." This one point, according to Dobson sensei, is the protective spirit, ki, which is employed in unraisable body exercise. But ki also is one's "connection to all life, time, and space; nowness; and energy". Throughout his life, Dobson sensei has been the mechanic for a more down-to-earth kind of ki. "Aikido in Everyday Life" was written to solve life conflicts by Aikido techniques. As he wrote "It is possible for a liar or a cheat to use Aiki or any of otherfive attacks to responses and aim for a 'kill' or a 'win' over somebody who has made the mistake of attacking him. But strange things begin to happen to people who become involved with Attack-tics ... even the most mean spirited of people begin to relinquish their grasp on their aggression, lose their anger, and reconnect with the living force". From his well known story "A Kind Word Turneth Away Wrath", one can see that the essence of Aikido according to Dobson sensei has a strong social implication. It seems that Dobson sensei's concept of ki covers all three definitions mentioned above.

oderick T. Kobayashi

Roderick T. Kobayashi was born in Hawaii and raised in Japan by his grandfather who was a Buddhist priest. Since his youth, he had been deeply involved in learning the history and philosophy of budo (Japanese martial arts).

Roderick T. Kobayashi was born in Hawaii and raised in Japan by his grandfather who was a Buddhist priest. Since his youth, he had been deeply involved in learning the history and philosophy of budo (Japanese martial arts).

He was first introduced to Aikido by his father who had great influence in invitingMaster Koichi Tohei, who was then Chief Instructor of Aikido at the Aikido World Headquarters in Japan, to Honolulu in 1953. However. his formal training in Aikido did not start until 1957, after his 3 years of military service. His first teachers at the Hawaii Aikikai were master:Yukiso Yamamoto, Kazuto Sugimoto, and Isao Takahashi. These masters were the first students of Tohei Shihan, the foremost authority on Aikido and Ki in the United States. Each of these masters was unique in his own way, and had a great influence in Kobayashi's understanding of Aikido and Ki.

Kobayashi's training with Master Tohei began in 1961. He trained under Tohei Sensei whenever possible in Japan, Hawaii and the continental U.S. He received his Shodan (1st degree black belt) in 1962, Nidan (2nd degree) in 1965, and San dan (3rd degree) in 1966. After becoming a full time professional Aikido instructor in the fall of 1968, he was promoted to the rank of Yondan (4th degree). He was also appointed as one of the two non-Japaneese nationals to receive the rating of Hombu Shidoin, instructor of Aikido for the Aikido World Headquarters, Tokyo, Japan. He assumed the responsibilities of the President and Chief Instructor of the Western States Aikido Federation until 1974. He was promoted to the rank of Godan (5th dan) in January, 1972. In September, 1973 Kobayashi was promoted to Rokyudan (6th degree), or master teacher.

As Master Tohei organized the Ki-no-Kenkyukai (Ki Society International) in 1971, Kobayashi was one of the most outspoken supporters of the Ki training program and the applications of the Ki principles in Aikido and daily life. In January, 1973. he was appointed as Koshi (full lecturer) of the Ki-no-Kenkyukai and received the certificate of Okuden (certification of completion of the innermost training in Ki).

In May, 1974, when Master Tohei founded his own system of Aikido, Shishin Toitsu Aikido, Rod Kobayashi began assuming the responsibilities of both the Chief Lectureship of Ki Development and the Chief Instructor of Shinshin Toitsu Aikido of the Ki Society Western USA.

Kobayashi began lecturing for the Physical Education department of theCalifornia State University, Fullerton in 1972. His goal was to establish a program at the University which would develop and certify well trained instructors of Aikido and Ki.

Rod Kobayashi has conducted numerous workshops throughout the United States, Israel, Russia, Europe, and Mexico. However, his main contribution was the founding of the Aikido Institute of America in Los Angeles, California. It was established for the purpose of developing instructors of Aikido in the United States. He emphasized the principles of Aikido; the Principle of Oneness which the founder, Master Morihei Ueshiba has professed and thePrinciples to Unify Mind and Body which, Master Tohei compiled.

The teaching methods at the Institute are designed for developing instructors. The instructors who are trained at the Institute are fully qualified to instruct the principles and the techniques of Aikido. Furthermore, the Institute emphasizes the application of the Aikido principles in daily life. Kobayashi strongly believed that Aikido instruction in the United States should be trained in the United States.

In March, 1981. Rod Kobayashi resigned from the Ki Society International and branched out to establish his own system of Aikido: Seidokan Aikido. Seidokan Aikido emphasizes the balanced practice of principle and techniques. The purpose of the system is to further develop Aikido so that it is better suited for the modern way of life.

The Doshu has accepted Seidokan Aikido as a legitimate system of Aikido. He and Kobayashi Sensei agreed that they shared the same goals and accepted the same fundamental principles of Aikido.

In February. 1989. Rod Kobayashi and his associates organized the Seidokan Institute, Inc., a non-profit California corporation to share the principles of Seidokan Aikido to those who wish to learn them and apply them in their everyday lives without the practice of self-defense arts.

On June 17th, 1995, Kobayashi Sensei passed away at his home in Downey, California. Seidokan continues on today in the memory of Kobayashi-sensei.

References:

W.-T. Chan, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, Princeton University Press, 1973.

Y.-L. Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, McMillan Press, 1966.

T. J. Kaptchuk, The Web that has no Weaver. Understanding Chinese Medicine, Congdon and Weed, New York, 1983.

W.-M. Tu, Confucian Thought, State University of New York Press, 1985.

S.-C. Huang, Chang Tsai's concept of Chi, Philosophy East and West, vol. 18, pp. 247, 1968.

Y. S. Kim, The Concept of Chi in Chu Hsi's philosophy, Philosophy East and West, vol. 34, 1984.

Y. Sakade, Longevity Techniques in Japan. Ancient Source and Contemporary Studies, in Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques, Eds. L. Kohn and Y. Sakade, Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan, 1989.

Morihiro Saito, Traditional Aikido, vol I-V, Minato Research and Publications 1974.

Morihiro Saito, Aikido, its Heart and Appearance, Minato Research and Publications 1975.

Yoshimitsu Yamada, The New Aikido Complete, Carol Publishing Group 1981

Gozo Shioda, Dynamic Aikido, Kodansha Publishing 1968. Translator: Hamilton Jeffrey.

Stan Prannin in Aikido and the New Warrior, Eds. Richard Heckler and Goerge Leonard, North Atlantic Books 1990.

The Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, An Outline of Chinese Acupuncture, Foreign Langauges Press, 1975.

Felix Mann, Acupuncture. The Ancient Chinese Art of Healing and How it Works Scientifically, Vintage Books 1973.

Shizuto Masunaga with Wataru Ohashi, Zen and Shiatsu. How to Harmonize Yin and Yang for Better Health, Japan Publication 1977.

Toru Namikoshi, Shiatsu and Stretching, Japan Publication 1985.

George Leonard, The Ultimate Athelete. Revising Sports, Physical Education and the Body, The Viking Press 1975.

Richard Strozzi Heckler, The Anatomy of Change. East/West Approaches to Body/Mind Therapy, Shambhala Publication 1985.

Terry Dobson and Victor Miller, Aikido in Everyday Life, North Atlantic Books 1983.

Aikido Today Magazine, The Journal of the Martial Arts and Spiritual Discipline of Aikido, #25, vol. 6 1992/1993.